The Complexity Versus Value Trap

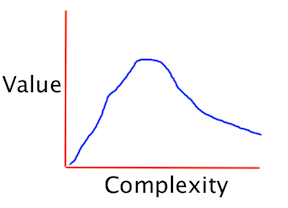

There is not a linear relationship between the complexity of a product’s features and the product’s value to an end user. The graph of complexity versus value often looks like this:

However, complexity in products is ubiquitous. Think about the products you use everyday — how many features, buttons, modes, and dials do they have which you never use or have no idea what they do? (I write this as I stare at a ‘checkmark’ button on my desk phone. I have never pressed it, nor do I know what it does).

That begs the question: Why do we build products whose complexity lies well past the inflection point of value on the graph above, when value is already decaying?

Here are my thoughts:

-

Building a complex product is rewarding for the builder. It requires solving challenging problems, which stimulates your brain and gives you gratification. This is problematic — products are built to solve a customer problem or need, not to satisfy your personal need for a challenge.

-

As a product becomes more complex, it inherently becomes more unique. Adding features to a product makes it less likely that another product has exactly the same combination of features. Produce uniqueness by combinatorial mathematics is bad — it causes customer confusion and does not add value. However, it is dangerously easy to convince yourself that because something is unique, it must also be valuable.

-

Accumulation and consumption are ingrained into our social behaviors. Marketers tell us they are positive behaviors (More! Bigger! not Less! Smaller!). The accumulation and consumption mindset is hard to ignore when building product, so it bleeds over and you accumulate features.

We build products with complexity, yet often times we just want simplicity. Why do we really just want simple things? Why do complex things really have less value?

- We want simple, specific products because we are trying to complete specific jobs. There is an emerging theory about this called ‘Jobs to be Done’ (JTBD). Clayton Christensen teaches us that customers don’t buy products, they hire a product to do a job or solve a fundamental problem. A great example of JTDB is this quote from Theodore Levitt:

‘People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!’ If we can map a product solution directly onto a problem we have, then our mental burden is reduced. If instead, we have to map a set of features in a complex product onto how it might solve our specific problem, this mapping task becomes a mental burden.

- There are many things competing for our attention each day. Additional complexity in product means additional required comprehension to understand product usage. We spend unnecessary effort understanding how to solve a problem with a product instead of actually solving a problem with a product.

I am not immune to the problems listed above. At my core, I am a builder. I feel satisfied when I build something, irrespective of the customer need for it. Unfortunately, if you build something and you ignore customer need, you have a side project, not a company or business. You need to actively avoid these behaviors. You need to con yourself into building simple things that solve specific customer problems. So how can you do it?

Here are a few simple ways to con yourself:

-

Define the Job To Be Done up front - This is not a list of features — this is the specific job your product will accomplish (e.g. make a quarter-inch hole). With a solid definition, you have an easy filter for product feature decisions. For every decision, ask yourself: does this contribute to job completion or does this make job completion more complex and convoluted?

-

Reflect often on the tools you use to accomplish your daily jobs to be done. What jobs are they accomplishing and why do you like those tools? (e.g. Why do you use Google and why do you like it?) - This will shed light on what you value as the consumer — maintain this mindset when you are the builder.

-

Learn how to say no to product feature requests. When people give you feedback on an idea, sometimes it’s just to fulfill their need to stimulate their own brain with invented complexity, not because they need the feature (hey, check out this great idea!). A good filter for this is to ask: How have you accomplished what you are trying to solve in the past? If they haven’t previously tried to accomplish the same goal in some cobbled together fashion, then it’s unlikely they have a strong need to solve the problem. Further, if a feature is actually important, the request will come up more than once, so pay attention to the requests you hear over and over again.

We never set out to build overly complex things, but we often end up with them. There is no complexity switch that gets flipped from off to on, it is a continuous process whose obviousness is only visible at the end. You have to take a conscious effort to avoid it all along the way.